The Elderhostel Institute Network: An Interview with Former Director Jim Verschueren

A decade before Elderhostel arrived on the scene, a radical shift in how society viewed older adults began germinating. Seniors — expected to sit in the corner and knit or play bingo — were rising from their chairs and taking an interest in learning and doing something new and exciting in their retirement years.

Federal legislation for adult education began in 1964 as this new way of thinking gained momentum. It was a time of empowerment and liberation as older individuals realized they still had much to contribute and learn. While a few organizations and universities — including UCLA, Harvard and Duke — were sprouting programs in response to this growing phenomenon, it wasn’t until Elderhostel was born in 1975 that the Lifelong Learning Movement became, in fact, a movement.

UCLA formed the Peer Learning and Teaching Organization (PLATO), while Harvard and Duke went by the Institute for Learning in Retirement (ILR). At UCLA, “a highly educated group of purists were shepherded by university faculty,” says Jim Verschueren, former director of the Elderhostel Institute Network (EIN). “These were peer-taught groups, and no one received pay.”

The UCLA group spawned other West Coast groups and formed the Association of Learning in Retirement Organizations West (ALIROW), a West Coast governing organization. They connected with East Coast ILRs to create an East Coast chapter. Those interested were the University of Delaware, the University of Rochester, Harvard University and Duke University.

These organizations shared common values and goals, rejecting negativity around aging and embracing learning as fulfilling and enriching for adult students. It made sense for Elderhostel to partner with them in trying to bring educational programs for retirees to their local areas.

While like-minded, the two organizations did not develop at an equal pace, as author Eugene S. Mills describes in his book, “The Story of Elderhostel”:

By the mid-1980s, Elderhostel was growing at an astonishing rate of 20% to 30% per year, while the Institute program was expanding much more slowly. Furthermore, Elderhostel had established a balance between decentralized programming and a highly centralized national headquarters, but the Institute Movement had no real center.

By forming lifelong learning institutes, older adults could explore new interests, engage in intellectual discussions and continue their education well into their golden years. It was a time of remarkable transformation as the boundaries of aging and learning were challenged and redefined.

A Star is Born: The Elderhostel Institute Network (EIN)

Institute program leaders nationwide had tried unsuccessfully to coordinate their efforts nationally for years. By the mid-1980s, the early visionaries of the movement were overwhelmed with requests to help start programs. Meanwhile, the Elderhostel administration was aware of the mutual benefit the two programs could offer each other. On June 12 and 13, 1986, leaders from both organizations met to discuss the idea of Elderhostel serving as a national coordinating organization for the Institute Movement. The meetings led to the establishment of the Elderhostel Institute Network (EIN) on Oct. 21, 1987.

The newly formed EIN was guided by the Institute Network Advisory Committee, chaired by Henry Lipman, and led daily by Jim Verschueren. No newcomer to Elderhostel, he began running Elderhostel programs at Franconia College, where he served as the director of admissions, in 1976. In 1978, when Franconia closed, he moved to New England College, where he coordinated 45 programs through 1983. He also became assistant director of the New England Regional Elderhostel office, based at the New England Center for Continuing Education of the University of New Hampshire, in 1983.

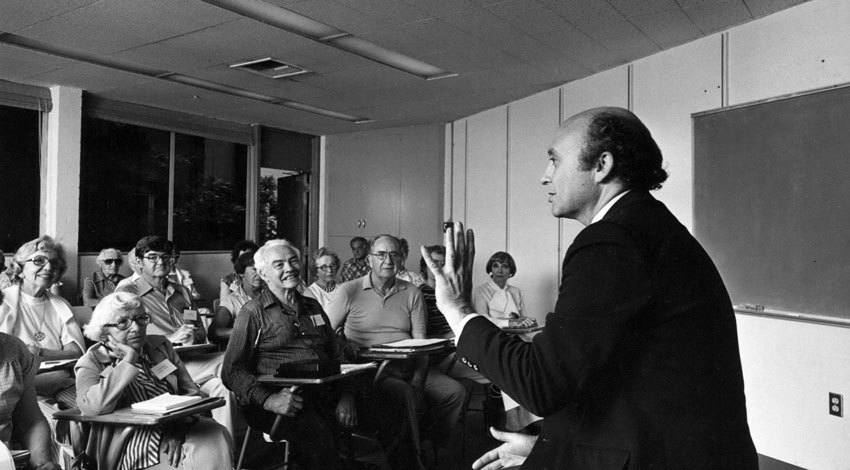

In 1987, Jim began a new role as director of the Institute Network. He focused his energy and experience on working with existing program leaders and conducting development workshops across the country to promote the creation of new programs. “We were determined not to feed into the myth that older people aren’t capable,” says Jim. “When Elderhostel began, people still thought your brain started to decline in your 20s.”

Elderhostel was pivotal in proving this myth was wrong.

“We gave people a reason to be positive and enjoy life,” says Jim. “That was the wonderful part of the work I was doing. It was exciting for me!”

Bill Berkeley, Elderhostel president from 1977 until the late 1990s, was a champion of the Institute Network when it started. “When the EIN started, he pushed Elderhostel to fund its growth,” says Jim.

“This is meaningful, and Elderhostel is uniquely positioned to expand this nationally.” Bill stressed that we were an organization that could expand the network, and that we should.

“We brought attention to something that wasn’t getting any attention, and in that sense, Elderhostel was the catalyst that propelled the Learning Institute Movement forward,” says Jim.

Jim’s formula for success rarely failed. “By the end of our meetings, the continuing education staff was on board and wanted to join the EIN,” he says. During his tenure as director (1987-1994), Jim expanded the movement to include nearly 300 institutions. Jim’s assistant director, Mary Linnehan, later became director of the EIN.

Traveling around the country, Jim found an eager audience for the EIN to grow at colleges and universities. “I visited different campuses and met with their continuing education department,” he says. “Many staff members had already heard about the EIN.” Nine out of ten times, he received a positive response. They were receptive to the idea and wanted to serve their community of adults.

“I never went alone; I brought an EIN member from another college to tell them how well the program was going for them,” says Jim. “We showed them what we were doing at the University of New Hampshire, explained what Elderhostel brought to the table, including a mailing list, and we gave them instructions on how to begin. The action was with Elderhostel — we could offer things they couldn’t do independently.”

Jim recalls visiting Young Harris College, a small liberal arts college nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains in northeastern Georgia. “They contacted me and said they had heard about the EIN, and they had a lot of retirees moving there,” he says.

About 40 people showed up for his presentation at the college. “I asked them how anyone found this place to retire,” says Jim. “They explained to me that they are J retirees — they had moved to Florida, hated it and curved back up like the letter J. I had never heard that term before, but they got a group together and joined the EIN.”

The Catalyst

“You can’t underestimate how influential Elderhostel was in the arena of older adults and travel — what an impact we had at one point on the Learning Movement,” says Jim. “Elderhostel served as the catalyst for the growth of the Learning in Retirement Movement and should take credit for it — that is what we did. Elderhostel drove educational travel, and other programs saw tremendous success and started following our formula,” he says. “This was a positive — the competition spurred Elderhostel to develop evermore creative programming.”

In the last 50 years, Elderhostel, now Road Scholar — after a thoughtfully planned name change in 2010 — has built the largest network of lifelong learning institutes (LLIs) across the United States, helping adults pursue their love of learning close to home.

Today, Road Scholar collaborates with administrators and members of more than 400 affiliated LLIs in our network to develop and share educational resources that help fulfill our shared educational missions. Most colleges and universities offer continuing education, some on their own and some under the Road Scholar umbrella.

“I believe in Road Scholar,” says Jim. “The fact that the organization made it through 9/11 and the COVID pandemic — when travel was shut down — and managed to stay alive and thrive means that whatever the organization is doing has been successful.”

Tracing Road Scholar's successes back to the beginning of our story, Elderhostel and the Elderhostel Institute Network were the mechanisms that sparked a new way of thinking about aging. “To me, it means staying engaged, never stopping growing or learning and staying open to new ideas,” says Jim. “At 77, it’s easy for me to say, 'I don’t like new music.' But I can’t shut down because things aren’t how they were in my 20s.”

Simply put, the Learning Institute Movement brought a new way of thinking for older adults. “Today, we expect to stay active; we don’t expect to get frail,” says Jim. “We’re taking more chances and enjoying life more.”

As a result of the Learning in Retirement Movement, hundreds of thousands of older adults participate in intellectual initiatives today. We are proud to carry this legacy forward as Road Scholar!